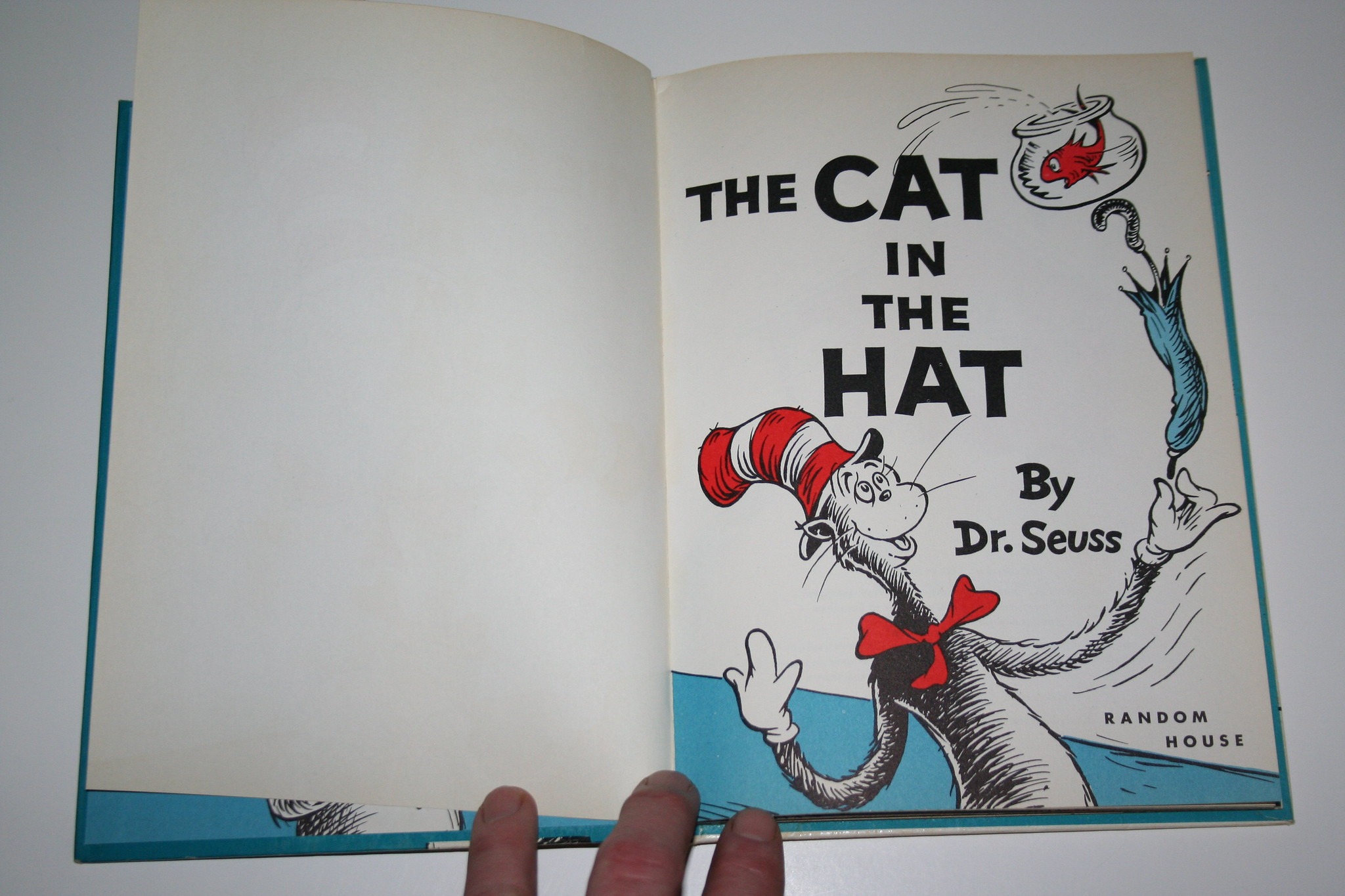

Did you know that when Dr. Seuss started to write ‘The Cat in the Hat,’ he felt overwhelmed by the constraints set by the publisher? The limitations that they imposed were challenging, to say the least. The story could only have a maximum of 200 words, and the publisher included a list of only 350 different words that could be used. Crucially, the story needed to be engaging and lively for children learning to read. Nonetheless, Dr. Seuss managed to overcome these restraints to create ‘The Cat in the Hat,’ a classic, childhood-favourite book that has sold over 16 million copies.

Photo Credit: Daniel X. O’Neil via Flickr

Often, we see constraints as hurdles to great creativity. We perceive them as obstacles that will impede us from creating something that otherwise could be better. In most instances, constraints are related to circumstance or context. They can include deadlines, tangible aspects that make a task physically impossible, or rules that need to be accepted. Constraints can also be self-created or appear in the form of mental roadblocks. Like when we tell ourselves that it’s the constraints that are limiting the depth and breadth of an idea. Or, that constraints create too much compromise and take away from the quality of the final result. At the end of the day though, it doesn’t matter where constraints come from. What’s more important is understanding how to work with and through them to minimise their disadvantages.

When working through a challenge, there is a tendency to amplify constraints by focusing on them first. This can make them sound worse than they are. In many instances, constraints aren’t the enemy. On the contrary, research has found that they can boost creativity and problem-solving. They can help guide, innovate, and even inspire creative thinking.

Often though, we get stuck at the beginning of the creative process when constraints overwhelm everything else, as we focus more on what we can’t do, instead of what we can do. This is because barriers (aka constraints) have been clearly identified and articulated, whereas a solution remains unknown. Over time we start to see creative sparks fly, and we begin to think about ways to work around constraints or solutions to work through them. We connect our ideas in different ways (often by asking ourselves ‘what if’) and reframe the situation. This leads to new possibilities, and our focus moves to the core challenge. Yet the process of working through constraints is not easy. Time is spent chasing multiple ideas as they evolve, and then frequently having to let go of them or move in a different direction because they don’t completely work or solve the problem. But, when an optimal solution appears, discomfort turns to satisfaction or even joy! The constraints are harnessed, and the project can move forward.

To wrangle constraints, you need to get comfortable dealing with them. The best way to achieve this is through practice. Here are three exercises to get you started:

Exercise 1:

The 6-word story. Try to come up with a story that’s only six words long. If you want to make it easier, start with eight words, before trying six. For example, ‘The waves fought with each other.’

Exercise 2:

Without using directional words (right, left, north, up, down, etc.), explain to someone or write instructions for how to get from your kitchen to your letterbox.

Exercise 3:

The next time you eat a meal, try swapping the hands you typically use for your knife and fork.

By completing these activities (and others like them), you rehearse how to engage with constraints and become desensitised to the discomfort surrounding them. You also begin to use your energy to reframe a challenge to expose yourself to possibilities that were not initially obvious.

Like Dr. Seuss, all of us encounter constraints in the workplace and our daily lives. My top tips for working through them include:

- Be calm. Don’t let the stress (or fear) associated with a constraint take over your thinking. If you are focusing too much on the constraint, step away and do something else. Come back when you can balance the constraint in proportion to the challenge.

- Be open when free-thinking about solutions and workarounds. Don’t discount ideas straight away; instead, park them and let them simmer in the background. What might happen is that you’ll get another great idea and are then able to combine your thoughts into an optimal solution that accounts for the constraint without overemphasising its weight.

- Ask questions. Questions are tools for collecting information and reframing situations. It helps even if you are only asking questions to yourself. Write both your questions and your answers down (ideally, using pen and paper!)—the connection between your brain and hands when writing often brings clarifying insight.

Remember, constraints aren’t always bad and could lead to work that positively influences the world—just like ‘The Cat in the Hat’ did for millions of children learning to read. However, like Dr. Seuss, know when to ignore a constraint if doing so could create an even better result. In the end, ‘The Cat in the Hat’ had 236 words, instead of the originally allotted 200. Bravo, Dr. Seuss!